The kids are alright

It's 7pm when the kids knock on our door in Vietnam. They're nineteen and twenty years old. They could, depressingly, be our children. But they haven't got the wrong apartment. They've come to show us around their home city and give us a glimpse into how they live. So we sling River into the sling, stick a coat on Olivia and head out into the cold and chaotic streets of Hanoi.

Now let's get one thing straight. We hate tours. Sometimes, they're necessary, but for the most part, we resent being told what to look at, how long for and having every single known fact about it rammed down our throats. We despise being shuttled off buses and through temples at the speed of light. This, however, is different.

Hana and Frank are Hanoi Kids. Launched in 2006, Hanoi Kids is an organisation built to give Vietnamese university students a chance to practise their English language skills, and English speaking visitors a glimpse of the real Hanoi. They may have started as a small collective but the rave reviews and unique approach caused it to snowball into a success story and, according to Trip Advisor, the number one thing to do when you're in town.

The process is simple enough. You fill in a form online. You choose your tour. You can do the classics, the monuments and museums and things on the must-do lists. Or, and this is where it gets interesting, you can customise. A Hanoi Kid will, within reason, take you anywhere you want to go, do anything you want to do. So if you want to spend a morning temple hopping, cool. But if you want to go gig hopping one night, that's great too. As long as you specify what you want to do, they'll try their best to hook you up with a Hanoi Kid who's into what you're into.

It's also, incredibly, free. Yes, you cover all costs for yourselves and your Hanoi Kid, from entrance fees to food to cabs, and you can choose to leave a donation which goes back into the programme. But other than that, it costs you nothing.

We're on an evening street food tour. And Hana and Frank seem a little taken aback that we're up for pretty much anything. I get the feeling that some tourists want the sanitised version, but after stints in Kathmandu, Sri Lanka and Thailand, we want the real thing.

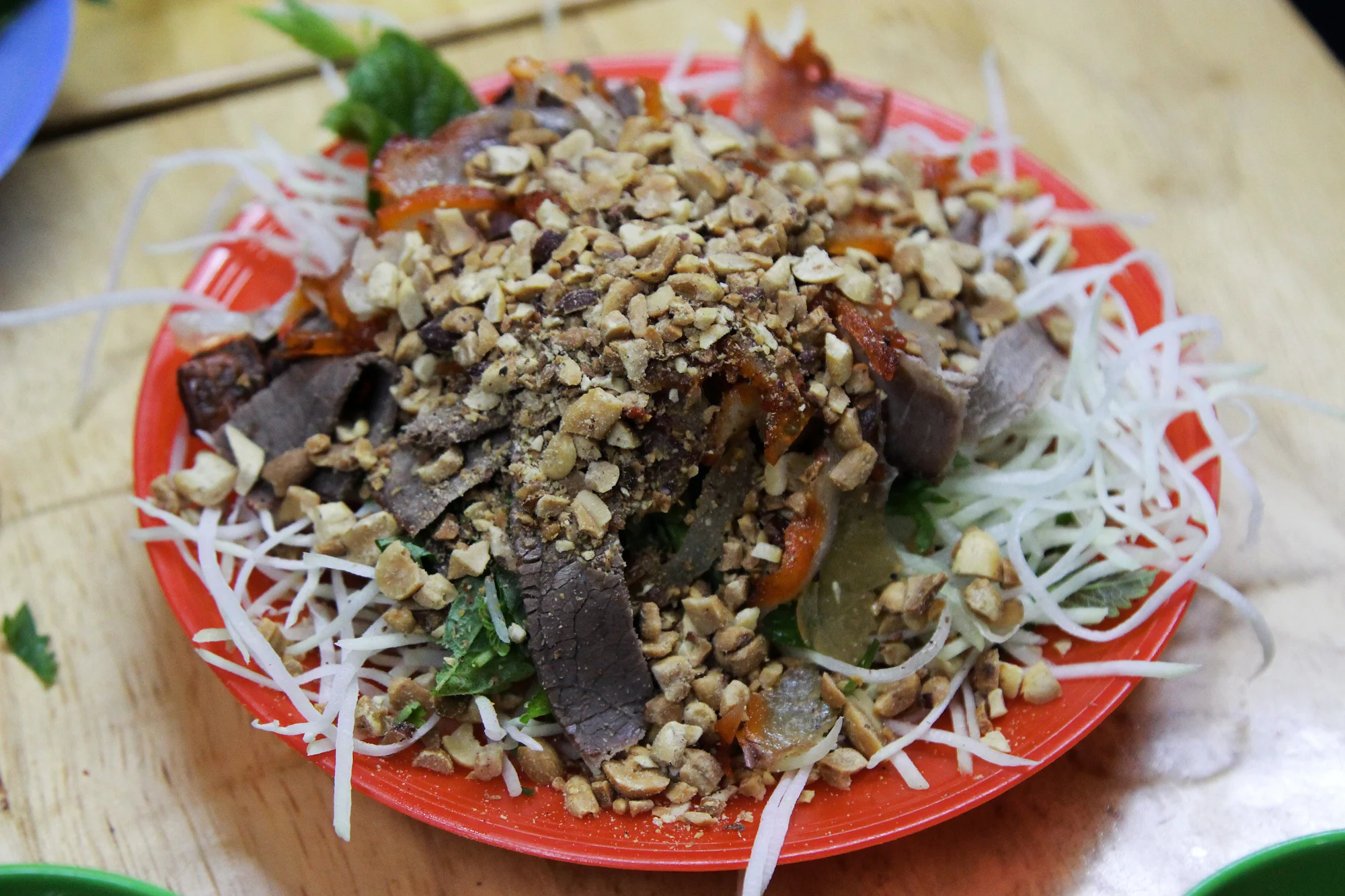

We start off in a restaurant of sorts, the kind over-populated by little blue plastic chairs, where you have to pop a few doors down to go and buy your beer. Under fluorescent tube lights, we eat translucent black mushroom dumplings and a punchy dried beef salad, both of which Olivia actually tries and River gobbles up like they're going out of fashion.

Next up, we stop suddenly in the middle of a dingy pavement. To our right is a tiny alley, containing four people, a giant Tupperware and a tiny fryer of ferocious oil, lacy spring rolls bobbing on its lethal surface. The rickety tables are the conveyor belt in this small but furiously fast factory, a man stuffing the savoury filing onto the casings, another wrapping them expertly with an experienced flick of the wrist. These are the special spring rolls made for the Tet holiday, which starts the following day, Hana tells us. We buy a dozen and munch them as we weave our way through the Friday night crowds, the paper bag turning glossy from the grease.

And that's the wonderful thing about Hanoi Kids. It's not just the discovery of places we would never have noticed alone, but the genuine immersion into a culture. Hanoians are famously, fiercely proud of their city, and these young, sharp, street-smart tour guides are referred to as 'little ambassadors'. They don't come with a glazed smile, a blank stare or an autocue script. They're just people, and they want us to know how they live.

So it's those in-between moments of chatter and confession that we fall in love with. As we negotiate another moped-rammed junction, we learn about the mother-in-law issues that young Vietnamese women face (hint: they don't want to live with them. Ever.) While waiting for our banh mi in a cosy booth, Trung cake cheats are exposed as we find out that most people can't be bothered with the romantic ritual of staying up all night to make the classic Tet recipe of pork and rice wrapped in leaves. We learn about families and politics, traditions and truths. It's a crash course in real life, but it doesn't for a second feel like a lesson.

We're supposed to be with Hana and Frank for three hours. It stretches out, over coconut coffee and easy conversation at Caphe Cong, to more like five. But there's still one question bugging us. They must be busy. And they don't get paid. So why do they do it?

Frank takes the question. "Well, yes, we get to practise our English. But that, for me is a very minor reason. The biggest reason is that we love to travel and we want to explore more, but it's so expensive to do it from Vietnam. So instead, we do this. It's not just us telling you about our place, it's you telling us about yours. It's an exchange. We get to learn about other cultures and other ways of living from all over the world. "

And with that, she hits the nail on the head. Because being a Hanoi Kid isn't a job. It's a passport.

HanoiKids

http://hanoikids.org/